Khipu (Quipu) and the Yupana

30/07/2018. Vladimir Esaulov

In 1956, Peruvian archaeologists uncovered a set of 21 knotted strings called khipu (or quipu in Spanish). The word khipu comes from the Quechua word for “knot”. The Incas relied on khipus to keep records of their extended empire. While the khipu stored numbers, the actual counting was presumably done using the yupana, the incan abacus. Studies are being performed by various groups to try to decode the khipus. A large database on khipus was established at Harvard by G.Urton (The Khipu Database project). There are more than around 800 surviving Khipus in various museums and a number in private collections. The use of khipus did not die out following the Spanish invasion but continued during colonial times. In a 1746 book Lorenzo Boturini wrote that such knotted strings were also found in Mexico and called Nepohualtzitzin. In recent years there appeared a theory by Mr. David Esparza that the Nepohualtzintzin was also an abacus with beads like the chinese one.

Somewhat differently made chord records existed from earlier, “Middle Horizon” (600-1000 AD) times, a period when there existed two dominant states: the Wari, in the central Andes, and Tiwanaku, in the south-central Andes. There is evidence that knotted cord records existed in much more ancient times. Archaeologist Ruth Shady Solis of the National University of San Marcos in Lima found an artefact in a pyramid in Caral-Supe (ref. UNESCO WHS). Caral is in the Barranca province (Perou); an archeological site with the earliest settlement dating prior to 26th century BC and thus considered as one of the oldest settlements in America. Amongst the artefacts found were woven carrying bags used in the carbon dating of the site, as well as a knotted textile object with pendant strings twisted around small sticks. It is thought that this might be an ancestor of the khipu.

Old texts dating from the time of the Spanish colonisation such as the “Parte Primera dela Crónica del Perú” (1553) of Pedro Cieza de Léon, “Codice Murua” (1590) of Martin Murua , “The Royal Commentaries of Peru” by Garcilaso de la Vega and the Guaman Poma de Ayala’s notes, “Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno” (16th century), give us some indications on the use of the khipu and the yupana.

Some Khipu’s. © Museo de Arte PreColombiana (Santiago, Chile).

The Middle Horizon Khipus (to be added).

Types of Andean/Incan Khipus.

There appear to exist two types of khipus: numerical and narrative.

Numerical khipus recorded economic and demographic data as wrote Garcilaso de la Vega (17th century) : they recorded “pasterlands, high and low hills, plough lands, estates, mines of metals, salt works, springs, lakes and rivers, cotton fields, and wild fruit-trees, and flocks… All these things and many others he (the Inca) had counted, measured, and recorded,” and also that “they had special accountants for all the affairs of peace and war, for the numbers of vassals, tributes, flocks, laws, ceremonies, and all else that had to be counted.”

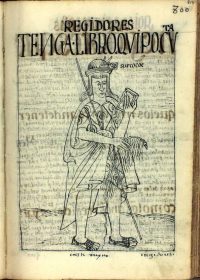

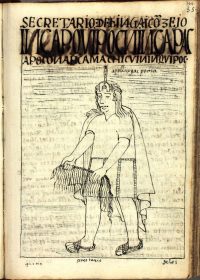

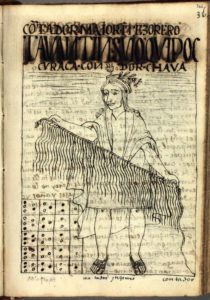

Narrative khipus, on the other hand, in some manner, recorded prose and poetry. “Treating their knots as letters, they chose historians and accountants… to write down and preserve the tradition of their deeds by means of the knots strings and colored threads, using their stories and poems as an aid,” wrote Garcilaso. As illustrated in some images here, Chaski messengers running in relay along the Inca road network carried khipus, transporting information between the capital and the provinces.

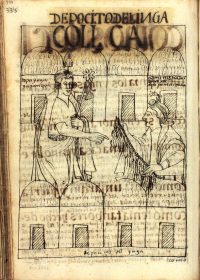

Cover and Some pages from Guaman Poma’s notes showing khipus. In image (d) the khipu in the hand on the messenger has a label “carta” (letter?).Images Courtesy: The Royal Danish Library, GKS 2232 4º kvart: Guaman Poma, Nueva corónica y buen gobierno.

Images of Quipus (khipus) and quipucamayos from the texts of Fray Martin de Murua. Courtesy Library Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. (a,b) source Historia y genealogía real de los reyes ingas del Piru 1590 and (c) Historia General del Piru 1616.

Khipu structure.

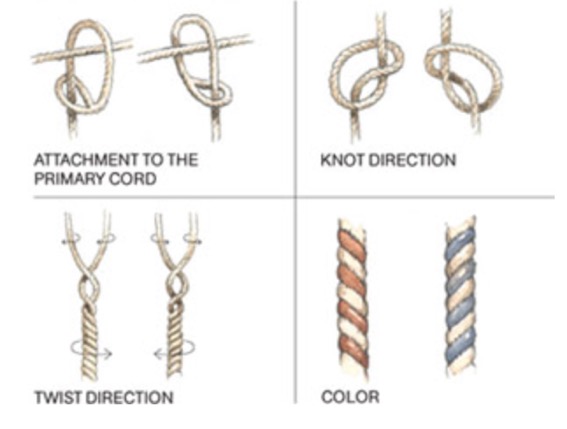

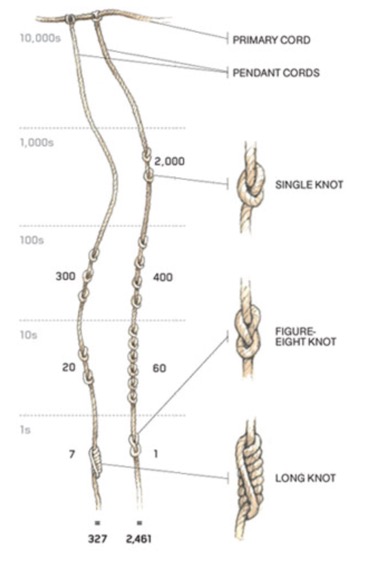

A khipu (usually of cotton, and more rarely of alpaca) consists of a main, thick primary, cord from which dangle a series of thinner pendant cords, with single, long, or figure – 8 knots (Locke 1912, Ascher 1997, Quilter and Urton 2002, Urton 2003, Ramos Vargas 2016).

The khipu is not only about knots. Encoded in the strings themselves and knots is information that apparently played a fundamental role in the “reading” of khipus:

The pendant cords could have subsidiary pendant cords on the side. Besides these there were also what are called “top” cords, which went up with respect to the downward going pendant cords. These were directly attached to the top primary cord, but could also unite several pendant cords passing trough the top loops of these. A nice detailed description can be found in the book of Asher and Asher (1997).

Colonial era khipus shed some light.

It is difficult to arrive at very definite conclusions about what a khipu documents, without additional supportive materials. Recently such a study relating a few khipus to written census documents from 1670, was described by Medrano and Urton (2018) and might help in further unravelling the khipu mysteries. In another recent work, Sabine Hyland (2017) analysed two 18th century khipus, claimed by local people to be tales of warfare, and concluded that they contained close to a hundred symbols, which could point to a narrative in a logocyllabic writing system:a combination of phonetic and ideographic symbols. However, these exciting studies relate to post Spanish invasion objects, which might affect the generality of interpretations that are made, in relation to older khipus.

The Yupana

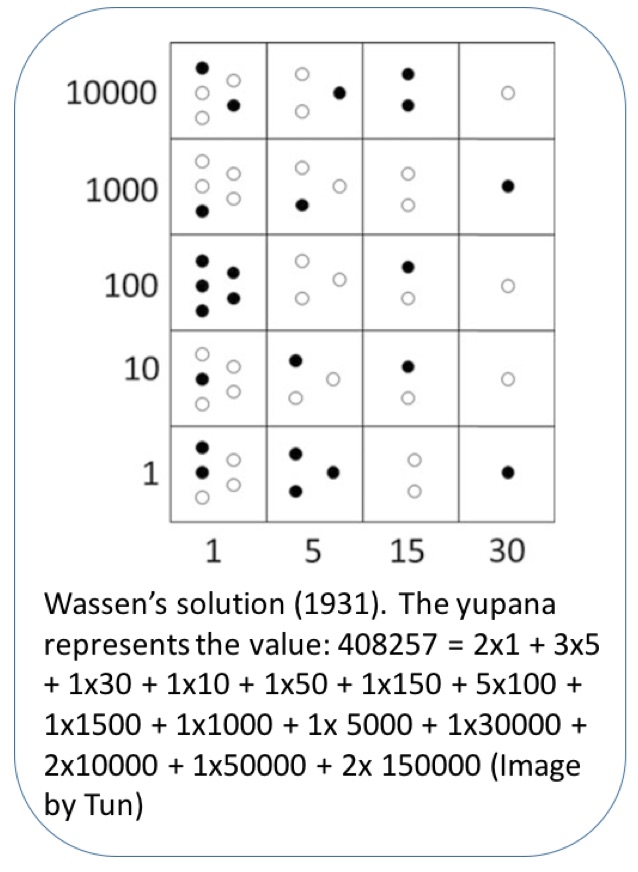

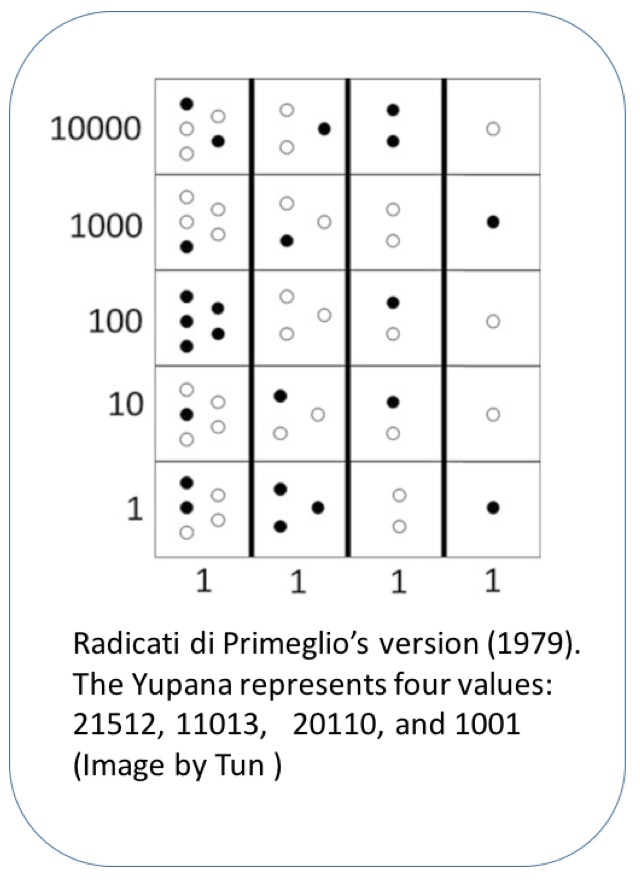

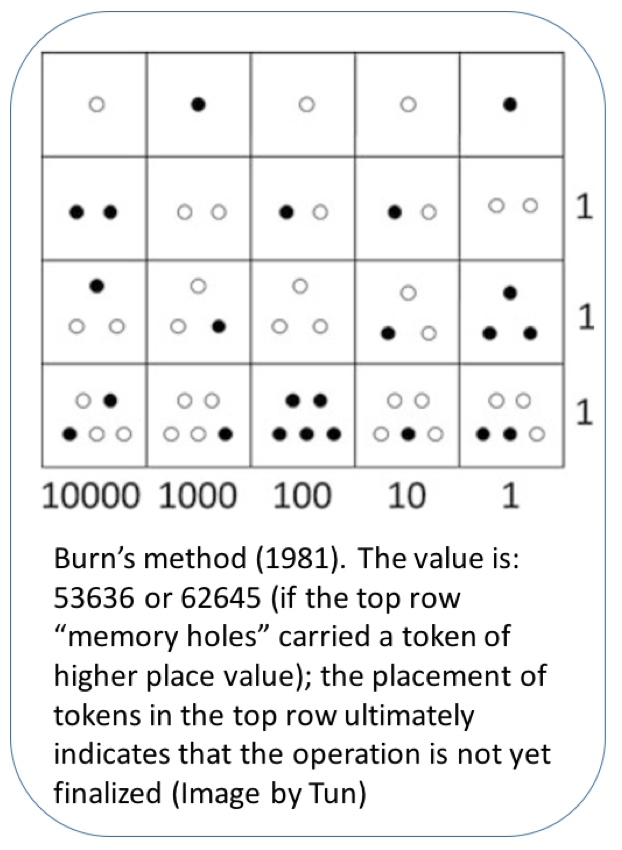

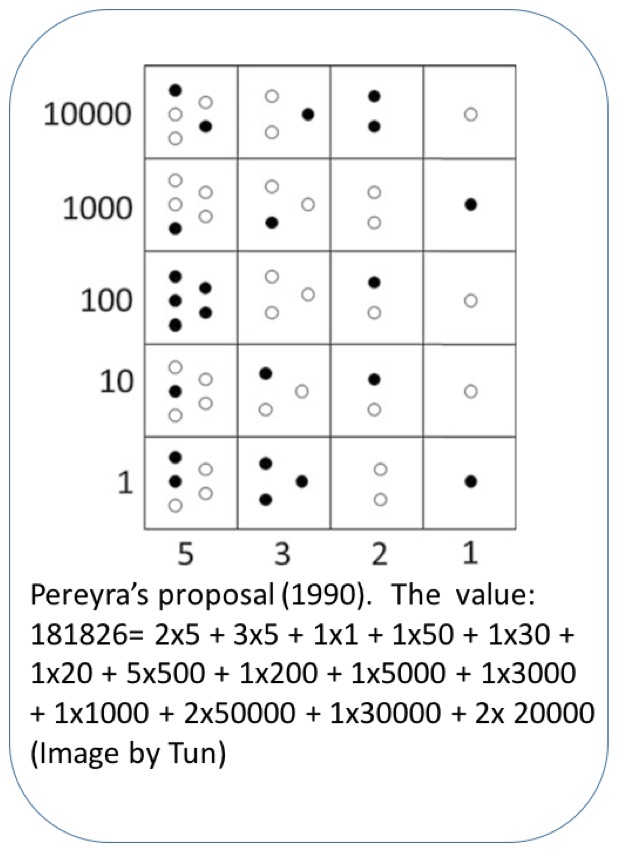

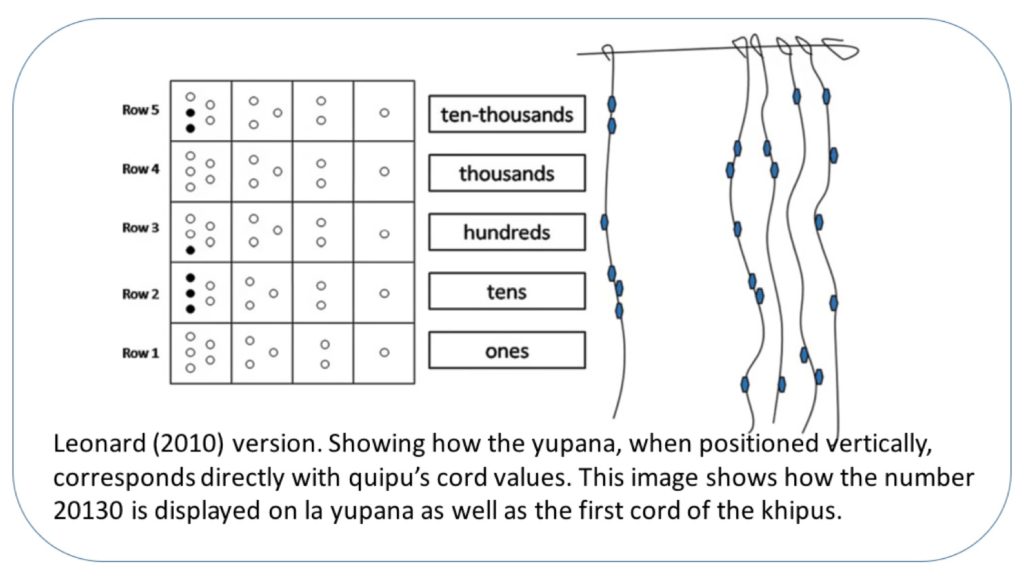

Not much is known about the ancient Incan abacus: la yupana (Radicati di Primeglio 1976, Lau 2016). In the indigenous Andean language of Quechua, “yupay” means “to count.” It was a tablet upon which stones, grains, or beans were placed and manipulated to perform calculations. While the khipu knot records were registries of amounts calculated, the yupana was used to calculate the amounts knotted into khipu cords. A drawing in the book of Guaman Poma, shown below, illustrates a kihpu and a checkerboard with points that is supposed to be a yupana (on theright below; click image to enlarge). The checkerboard has twenty rectangles with each row showing from left to right five, three, two and one white & black dots. It has been suggested that this was used to count using grains as counters, in a base ten or even base 40 systems (in which case the dot (counter) would correspond to a count of five.

Besides the sketch in Guaman Poma’s chronicles, there is no reliable information about the actual structure of the boards used for the calculation, besides a comment in a later text of Juan Velasco, the “History of the Kingdom of Quito” where a mention is made of some type of “boards” made of wood, stone or clay, which had various compartments, in which were placed pebbles of different sizes, colors and shapes.

In 1869 a wooden board, with some points in common to that mentioned by Velasco, was discovered near Chordeleg (province of Cuenca, Peru). The board had a number of square and rectangular compartments (holes) in a flat region and two two level tower like structures on diagonally opposite sides of the board. A number of other such terraced boards and also flat boards with indented divisions, made of wood, stone and bone have been found and are illustrated and commented in the following. A number of these boards are from periods much before Incan times (Lau 2016). It has been suggested that these could be : (i) architectural models, (ii) counting boards (yupanas) or (iii) game boards (taptanas). The idea of the former type as architectural models has been more or less abandoned. The fact that many of these have a dual symmetric (antisymmetric) structure points to the fact that they were either meant to be used by two players or else to count “income” and “expense”. Which of these two uses is correct is still being debated (see Radicati 1976 and Lau 2016) and might depend on the board in question. Game boards of a similar flat type with a series of symmetrically placed compartments for two players (but without tower structures) are known to exist from ancient times in other cultures like the 20 square game boards (Game of Ur & others), the still played games in Africa ( Mancala board (and other names), and Asia (e.g. the Palankuzhy board in Kerala, India), etc.

How was the yupana used ?

The Spanish missionary José de Acosta describes (1586) the Inca counting system: “To see them use another kind of quipu with maize kernels is a perfect joy. In order to carry out a very difficult computation for which an able accountant would require pen and ink. . . these Indians make use of their kernels. They place one here, three there and eight I do not know where. They move one kernel here and three there and sure enough, they are able to complete their computation quickly without making the smallest mistake. As a matter of fact, they are better at calculating what each one is to pay or give than we would know how to check with pen and ink. Whether this is not ingenious and whether these people are wild animals let those judge who will! What I consider as certain is that in what they undertake they have great advantage over us.“

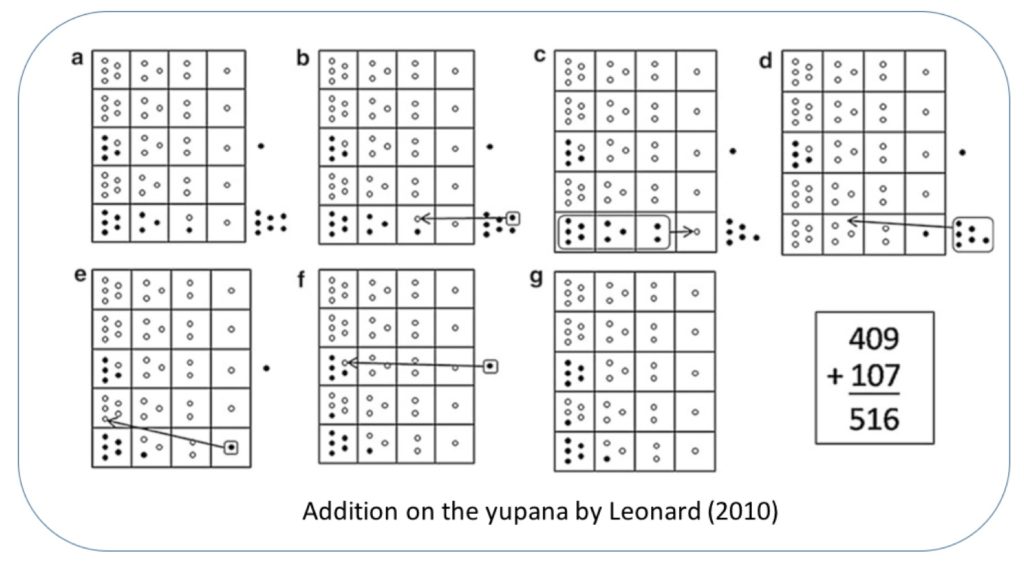

There are several theories about how the yupana was used. They are mostly concerned with the board illustrated by Guaman Poma. Some of these are illustrated here without further comments (see details in M. Leonard and C.Shakiban, 2010; M. Leonard 2011). This type of Yupana is used in schools in Latin America.

Examples of Andean boards. (to be added)

References.

Khipu Database Project by Gary Urton. https://khipukamayuq.fas.harvard.edu

Garcilaso de la Vega. 1688. The Royal Commentaries of Peru. https://archive.org/details/royalcommentarie00vega

- Guaman Poma de Ayala’s notes, “Nueva Coronica y Buen Gobierno”, The Royal Danish Library, GKS 2232 4º kvartd

- Murua, Martin.1590 ,Códice Murúa: Historia y Genealogía de los Reyes Incas del Perú del padre mercedario Fray Martín de Murúa: Códice Galvin http://repositorio.pucp.edu.pe/ and also @ Manuscrito Galvin.

Unesco WHS. The Sacred City of Caral-Supe (Peru) No 1269, Unesco World Heritage Centre document. https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1269.pdf

Locke L. 1912, The Ancient Quipu, a Peruvian Knot Record, American Anthropologist, New Series, V14, No. 2 , pp. 325- 332.

Ascher Marcia and Robert Ascher Robert. 1997 Mathematics of the Incas: Code of the Quipu. Dover Publications. ISBN-13: 978-0486295541. ISBN-10: 0486295540

Salomon, F. 2013. The Twisting Paths of Recall: Khipu (Andean cord notation) as artifact. In: Piquette, K. E. and Whitehouse, R. D. (eds.) Writing as Material Practice: Substance, surface and medium. Pp. 15-43. London: Ubiquity Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bai.b

Quilter, Jeffrey and Urton Gary (eds.). 2002. Narrative Threads, Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002.

Ramos Vargas, Mario A. Quipus y quipucamayos en el registro arqueológico: una evaluación desde Huaycán de Cieneguilla, valle de Lurín. Cuadernos del Qhapaq Ñan Año 4, N° 4, 2016 / issn 2309-804X

Urton, G., 2003. Signs of the Inka Khipu: Binary Coding in the Andean Knotted String Records. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003.

Medrano M. and Urton G., 2018, Toward the Decipherment of a Set of Mid-Colonial Khipus from the Santa Valley, Coastal Peru , Ethnohistory (2018) 65 (1): 1–23., https://doi.org/10.1215/00141801-4260638

Hyland Sabine, 2017. “Writing with Twisted Cords: The Inscriptive Capacity of Andean Khipus,” Current Anthropology 58, no. 3 (June 2017): 412-419.

Mackey Carol. 2002. The Continuing Khipu Traditions. Principles and Practices. Narrative Threads. ed J. Quilter and G. Urton, University of Texas Press

Velasco Juan, 1841. – “Historia del Reino de Quito” – 44, Tomo II, 7. https://archive.org/details/56663290HistoriaDelReinoDeQuitoEnLaAmericaMeridionalVol2/

Radicati di Primeglio, Carlos, 1976. El Sistema Contable de Los Incas. Yupana e Quipu. Libreria STUDIUM, lima, Peru.

- Lau. George F. 2016, An archaeology of Ancash: stones, ruins and communities in Andean Peru. Abingdon: Routledge; 978-1-138-89899-8

- Leonard M. and Shakiban C., 2010. The Incan Abacus: A Curious Counting Device, Journal of Mathematics and Culture, November 2010, 5 (2), 81-106

- Leonard, Molly. “The Incan Abacus: A Curious Counting Device.” Journal of Math & Culture, vol. 5, no. 2, 2011, pp. 81–106