Data Storage with Knots and Beads

30/07/2018. Vladimir Esaulov

The story of knots goes back into ancient history. One of the interesting ways to use them, was for recording events and accounting. One finds such use of knots in many regions around the globe.

- Chinese Knots

- Japan & Warazans

- Andean Khipu (Quipu) (Khipu and Yupana Main Page)

- Other Regions, the Wekui and the Wampum

Chinese Knots.

In Asia, China specifically, one finds references to knots as means of record keeping in old texts like the Ta Chuan, Book of Change, (the Great Commentary on the I Ching, 500-220 BCE) where it is said (Section II-13) :” In the highest antiquity, government was carried on successfully by the use of knotted cords to preserve the memory of things. In subsequent ages, for these the sages substituted written characters and bonds. By means of these the doings of all the officers could be regulated, and the affairs of all people accurately examined. The idea of this was taken, probably, from the hexagram Kuai”. Another example is in the Dao de Jing of Laozi from the time of the Warring States (box on the right).There are no known existing examples of these Chinese knotted records.

Dao De Jing / 80.(Standing alone),老子,Laozi/道德經

[Warring States (475 BC – 221 BC)]

There are several English translations of this text, which vary somewhet. Here we give the publicly open translation by James Legge

Japan and other Asia-Pacific Region.

Around the Pacific one also finds references to knots for recording:- in Japan, Hawaii, New Zeeland, in the Americas in particular in Peru: the Khipu. Interestingly in Japan on the Ryukyu islands people still used knots in the early 20th century: the Warazan (or barazan). These were made of plants, with rice straw as one of the main materials. They were used for recording taxes, in accounting etc. Their use decreased with spreading of education.

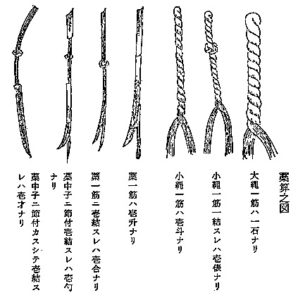

Some Warazans

Warazan, © Ridai Museum of Modern Science, Tokyo

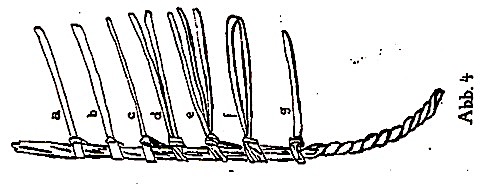

The village assembly. On the island of Yaeyama, this cord was used to establish the presence of persons authorized to participate in the popular assemblies. It concerns all male house residents over 15 years. Their number was first determined for each house and every street.

- House No. 1 (a) has only one eligible person.

- Likewise House 2 and 3 (b and c).

- In house 4 and 5 there are 2 and 3 claimants.

- The noose (f) means that the road here is broken by a crossroads.

- In the 6th house lives again only one eligible.

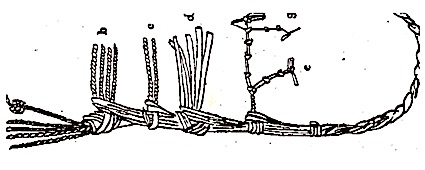

Torishimesan. The tax amount to be paid in rice is shown here.

94 koku, 2 to, 5 sho, 7 go, 8 shaku, 7 sai.

- The ends coming from the main strand have a value of 10 koku each.

- The loop corresponds to 50 koku.

- b= je1 koku, e = go, f = shaku, g = sai

To avoid mistakes, the strands are different in thickness. Images and comments above come from the German ethnologist, Simon Edumd’s article in “Asia Major”, Leipzig, 1924. Source BG and NGO

Some other Warazan from:

農政学から民俗学へ―笹森儀助の『南嶋探験』(1894)

Rural Economics to Ethnography: Sasamori Gisuke’s Exploration of the Southern Islands (1894). Source: Ebisu Reviews.

Peru and the Incan Khipu

In 1956, Peruvian archaeologists uncovered a set of 21 knotted strings called khipu (or quipu in Spanish). The Inca relied on sets of khipu to keep records of their far-flung empire, which extended more than 5500 kilometers from today’s south Colombia to mid Chile. This system of recording information existed much before the Incan times.

Much research is being done to try and understand how the khipus were used. They were the data storage medium, whereas the counting appears to have been done using the Incan abacus: the yupana. Click on the image to go to the khipu-yupana page.

Venezuelan Wekui.

Some ethnic groups in Venezuela used a single rope with a series of knots called Wekui, to keep track of the passage of days. This was first described by ethnographer Koch Grüemberg, who visited Venezuela at the beginning of the 20th century. He mentioned that they were made with woven palm leaves. The main function of the Wekuí was to keep track of the days on a trip, tying or untying knots. According to Sanchez (2009), these instruments were still used in the Wonken community, in southern Venezuela in 1989.

Knots in other countries.

Knots on ropes were used in various other places around the globe. Thus according to some sources (MIT talk by J.-J Quisqater: cryptographer and a professor at Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium.):-

In some African regions, women recorded the length of their pregnancy on a string, with a series of knots, so that, by loosening a knot at each full moon, they could predict the timing of their pregnancy. Also in Africa a man who left on a trip would leave his wife a cord with as many knots as days of absence. In this way, the woman, by undoing a knot every day, knows the date on which her husband will return.

The same countdown system, as reported by Herodotus, was used by the Persian king Darius I when, during a military operation, he left a 60-knot rope to the soldiers on guard at a bridge of great strategic importance. These soldiers were ordered to undo a knot every day and abandon the position when all the knots were defeated, whether or not the king returned.

In Europe, a curious numbering system with knots was used until the beginning of the 20th century by German millers. In order to indicate the quantity and type of flour contained in a bag, they made a series of knots to the string that closed the bag.

The Wampum.

The Wampum was used by many native peoples in the northeastern part of North America. Wampum is a shortening of wampumpeag, which is derived from the Massachusett or Narragansett word meaning “white strings of shell beads”. It consisted of purple and white beads made from the shells of quahog clams. The white shell beads stand for peace, friendship, and harmony. The purple shell beads represent war, suffering, or events of great importance. The beads were strung in single strands or woven into “belts”, like those made on bead-looms today. The wampum had social, economic, political and religious implications. The Iroquois used wampum as a person’s credentials or a certificate of authority. The founding constitution of the Iroquois Confederacy was codified in a series of wampum belts, now held by the Onondaga Nation.

The wampum were in particular used for recording and sending messages. The design on each string or belt indicated the type of message being sent and helped the messenger remember the specific contents.

- Top Image (click to enlarge): The Two Row wampum belt represents an agreement between the Haudenosaunee and the European Colonists.

- Bottom: The Hiawatha Belt is one of the most well known of the wampum belts. It is a symbol of the agreement between the five original Haudenosaunee nations and their promise to live in unity and stand by one another in times of trouble. The four white squares stand for the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca nations.

References.

Sánchez, D. (2009). El Sistema de Numeración y algunas de sus aplicaciones entre los Aborígenes de Venezuela. Revista Latinoamericana de Etnomatemática, 2(1). 43-68